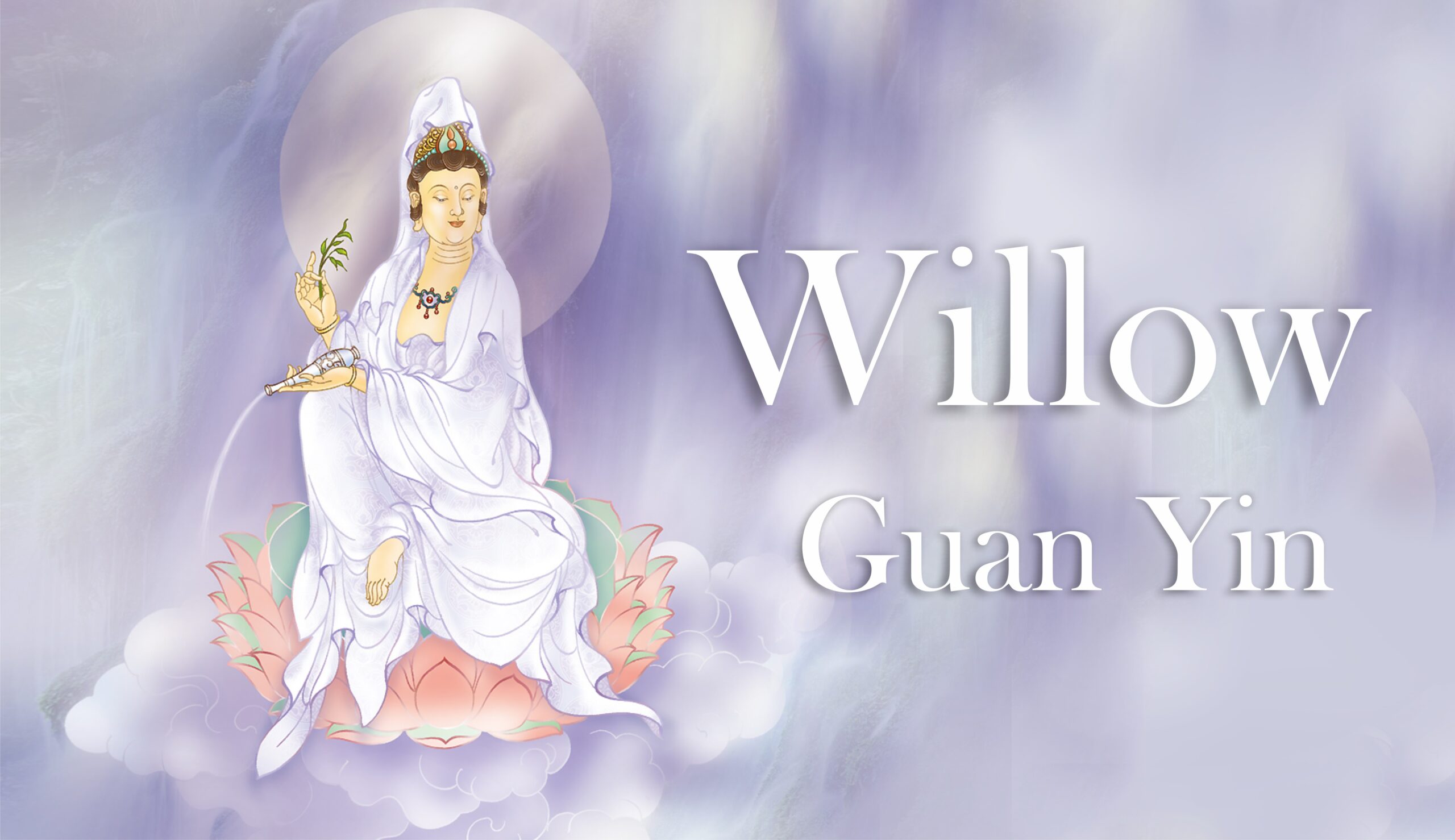

Willow Guan Yin

Medicine Guan Yin

Playful Guan Yin

THE GODDESS’ NAME

The name Guan Yin also spelt Guan Yim, Kuan Yim, Kwan Im, or Kuan Yin, is a short form for Kuan-shi Yin, meaning “Observing the Sounds (or Cries) of the (human) World”.

Highly respected in Asian cultures, Guan Yim bears different names as follows:

Hong Kong: Kwun Yum

Japan: Kannon or more formally Kanzeon; the spelling Kwannon, based on a pre-modern pronunciation, is sometimes seen

Korea: Gwan-eum or Gwanse-eum

Thailand: Kuan Eim (กวนอิม) or Prah Mae Kuan Eim

Vietnam: Quan Âm

In Chinese Buddhism, Guan Yin is synonymous with the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, the pinnacle of mercy, compassion, kindness and love.

(Bodhisattva- being of bodhi or enlightenment, one who has earned to leave the world of suffering and is destined to become a Buddha, but has forgone the bliss of nirvana with a vow to save all children of god.

Avalojkitesvara (Sanskrit: अवलोकितेश्वर): The word ‘avalokita’ means “seeing or gazing down” and ‘Êvara’ means “lord” in Sanskrit).

Among the Chinese, Avalokitesvara is almost exclusively called Guan Shi Yin Pu Sa. The Chinese translation of many Buddhist sutras has in fact replaced the Chinese transliteration of Avalokitesvara with Guan Shi Yin. Some Taoist scriptures give her the title of Guan Yin Da Shi, and sometimes informally as Guan Yin Fo Zu.

ORIGIN

Along with Buddhism, Guan Yin’s veneration was introduced into China as early as the 1st century AD, and reached Japan by way of Korea soon after Buddhism was first introduced into the country from the mid-7th century.

Representations of the Bodhisattva in China prior to the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD, Northern – and Southern Song Dynasty) were masculine in appearance.

It is generally accepted that Guan Yin originated as the Sanskrit Avalokitesvara, which is her male form, since all representations of Bodhisattva were masculine.

Later images might show female and male attributes, since a Bodhisattva, in accordance with the Lotus Sutra, has the magical power to transform the body in any form required to relieve suffering, so that Guan Yin is neither woman nor man. In Mahayana Buddhism, to which Chinese Buddhism belongs, gender is no obstacle to Enlightenment.

As the Lotus Sutra relates, the Bodhisattva Kuan Shih Yin, “by resort to a variety of shapes, travels in the world, conveying the beings to salvation.”

The representation in China was further interpreted in an all-female form around the 12th century, during the Ming Dynasty (1368- 1644 AD).

The twelfth-century legend of the Buddhist saint Miao Shan (see below), the Chinese princess who lived in about 700 B.C., is widely believed to have been Kuan Yin, reinforced the image of the Bodhisattva as a female.

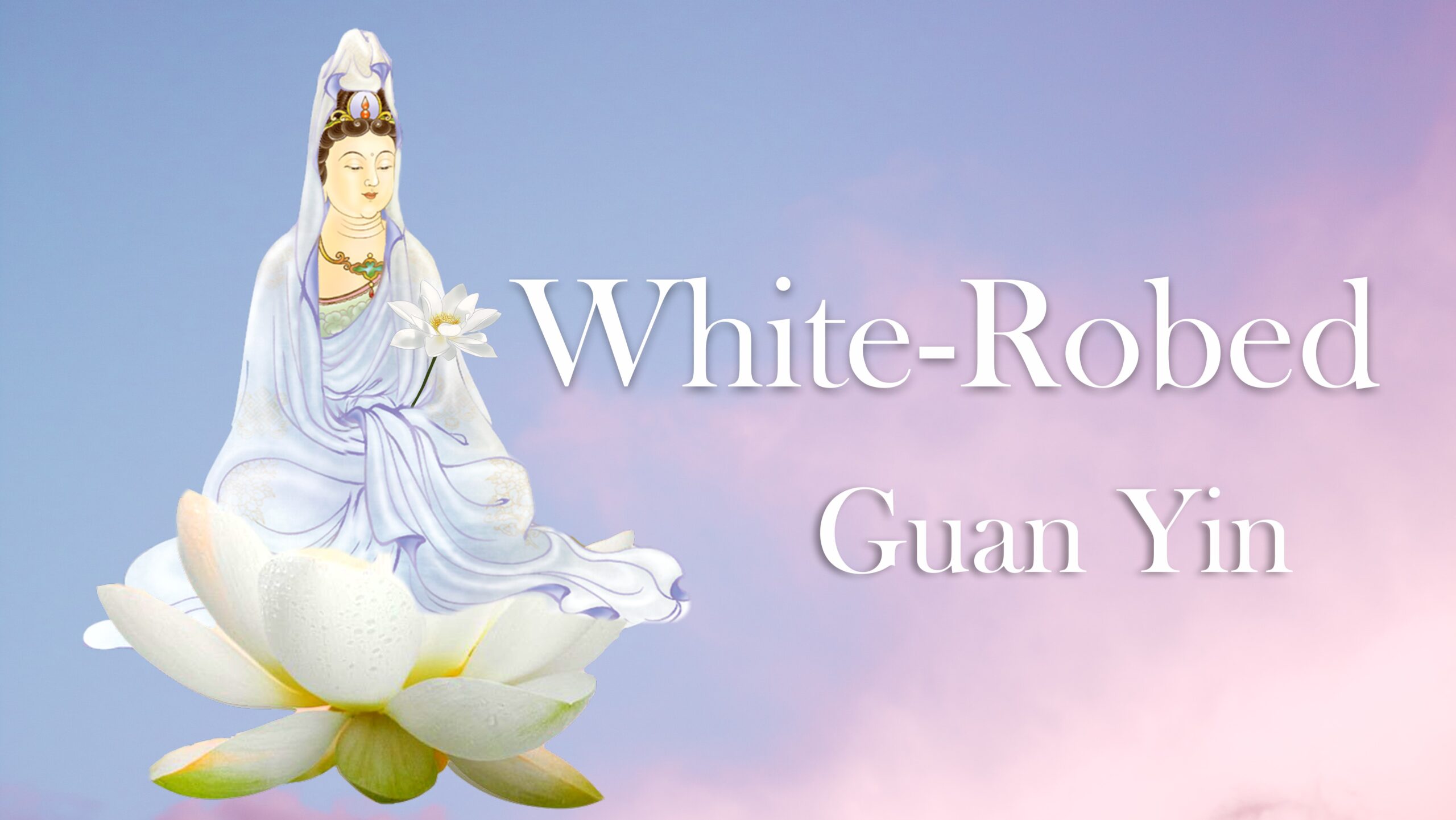

In the modern period, Guan Yin is most often represented as a beautiful, white-robed woman, a depiction which derives from the earlier Pandaravasini form.

In Sanskrit she’s known as Padma pani – “Born of the Lotus”, the lotus symbolizing purity, peace and harmony.

Another version suggests she originated from the Taoist Immortal Ci Hang Zhen Ren, (Chinese: 慈航真人; pinyin: Cíháng Zhēnrén; literally “Compassion Travel/Navigate True Person”), a Taoistic ‘perfect person’ having an endless willingness and sparing no effort in helping those in need.

Commonly known in the West as the Goddess of Mercy, Guan Yin is also revered by both the Taoists and Buddhists.

PORTRAYAL, APPERANCE

Guan Yin is usually shown in a white flowing robe – white being the symbol of purity -, and usually wearing necklaces of Indian/Chinese royalty. In the right hand is a water jar (as the Sacred Vase the water jar also one of the Eight Buddhist Symbols of good Fortune) containing pure water, the divine nectar of life, compassion and wisdom, and in the left, a willow branch to sprinkle the divine nectar of life upon the devotees as to bless them with physical and spiritual peace. The willow branch is also a symbol of being able to bend (or adapt) but not break. The willow is also used in shamanistic rituals and has had medicinal purposes as well.

The crown usually depicts the image of Amitabha Buddha (Fully Conscious Infinite Light), Guan Yin’s spiritual teacher before she became a Bodhisattva.

A bird, mostly a dove, representing fecundity is flying toward her.

A necklace or rosary is associated with her calls upon Buddha for succor, each bead of it representing all living beings and the turning of the beads symbolizes that Guan Yin is leading them out of their state of misery and repeated rounds of rebirth into nirvana, hence the beads represent enlightenment.

Should a book or scroll of papers be within the portrayal, it is representing the Dharma, the teaching of Buddha or the sutra, the Buddhist text, Guan Yin is said to have constantly recited from.

Guan Yin is often depicted either alone, standing atop a dragon, accompanied by a bird, flanked by two children, or flanked by two warriors. The two children are called Long Nue and Shan Tsai (see below). The two warriors are the historical character Guan Yu who comes from the ‘Three Kingdoms’ period and the mythological character Wei Tuo who features in the Chinese classic ‘Canonisation of the Gods’. The Buddhist tradition also displays Guan Yin, or other Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, flanked with the two said warriors, but as Bodhisattvas who protect the temple and the faith itself.

Guan Yin sitting on a pink lotus is a sign for peace and harmony.

GUAN YIM AND THE THOUSAND ARMS

One Buddhist legend presents Guan Yin as vowing to never rest until she had freed all sentient beings from samsara, reincarnation. Despite strenuous effort, she realized that still many unhappy beings were yet to be saved. After struggling to comprehend the needs of so many, her head split into eleven pieces. Amitabha Buddha, seeing her plight, gave her eleven heads with which to hear the cries of the suffering. Upon hearing these cries and comprehending them, Guan Yin attempted to reach out to all those who needed aid, but found that her two arms shattered into pieces. Once more, Amitabha came to her aid and appointed her a thousand arms with which to aid the many.

Many Himalayan versions of the tale include eight arms with which Avalokitesvara skillfully upholds the Dharma, each possessing its own particular implement, while more Chinese-specific versions give varying accounts of this number.

Like Avalokitesvara, Guan Yin is also depicted with a thousand arms and varying numbers of eyes, hands and heads, sometimes with an eye in the palm of each hand, and is commonly called “the thousand-arms, thousand-eyes” Bodhisattva. In this form she represents the omnipresent mother, looking in all directions simultaneously, sensing the afflictions of humanity and extending her many arms to alleviate them with infinite expressions of her mercy, while the thousand eyes help her see anyone who may be in need.

In other portrayals Guan Yin is shown with a peacock. The peacock is another manifestation of the heavenly Phoenix on earth. It has a hundred eyes on its tail feathers, symbolizing Kuan Yim’s thousand eyes.

GUAN YIM FLANKED BY TWO CHILDREN, GUAN YIM FLANKED BY LONG NUE AND SHAN TSAI

Guan Yin’s presence is widespread through her images as “bestowing children” which are found in homes and temples. A great white veil covers her entire form and she may be seated on a lotus, the sign for purity. She is often portrayed with a child in her arms, near her feet, or on her knees, or with several children about her. In this role, she is also referred to as the “white-robed honoured one.” Sometimes to her right and left are her two attendants, a girl called Lung-wang Nu, the daughter of the Dragon-king and a boy, Shan-ts’ai Tung-tsi, the “young man of excellent capacities” (see: Jade One and the Golden Child). The two children are her acolytes who came to her when she was meditating at Mount Putuo.

GUAN YIN STANDING ATOP A DRAGON

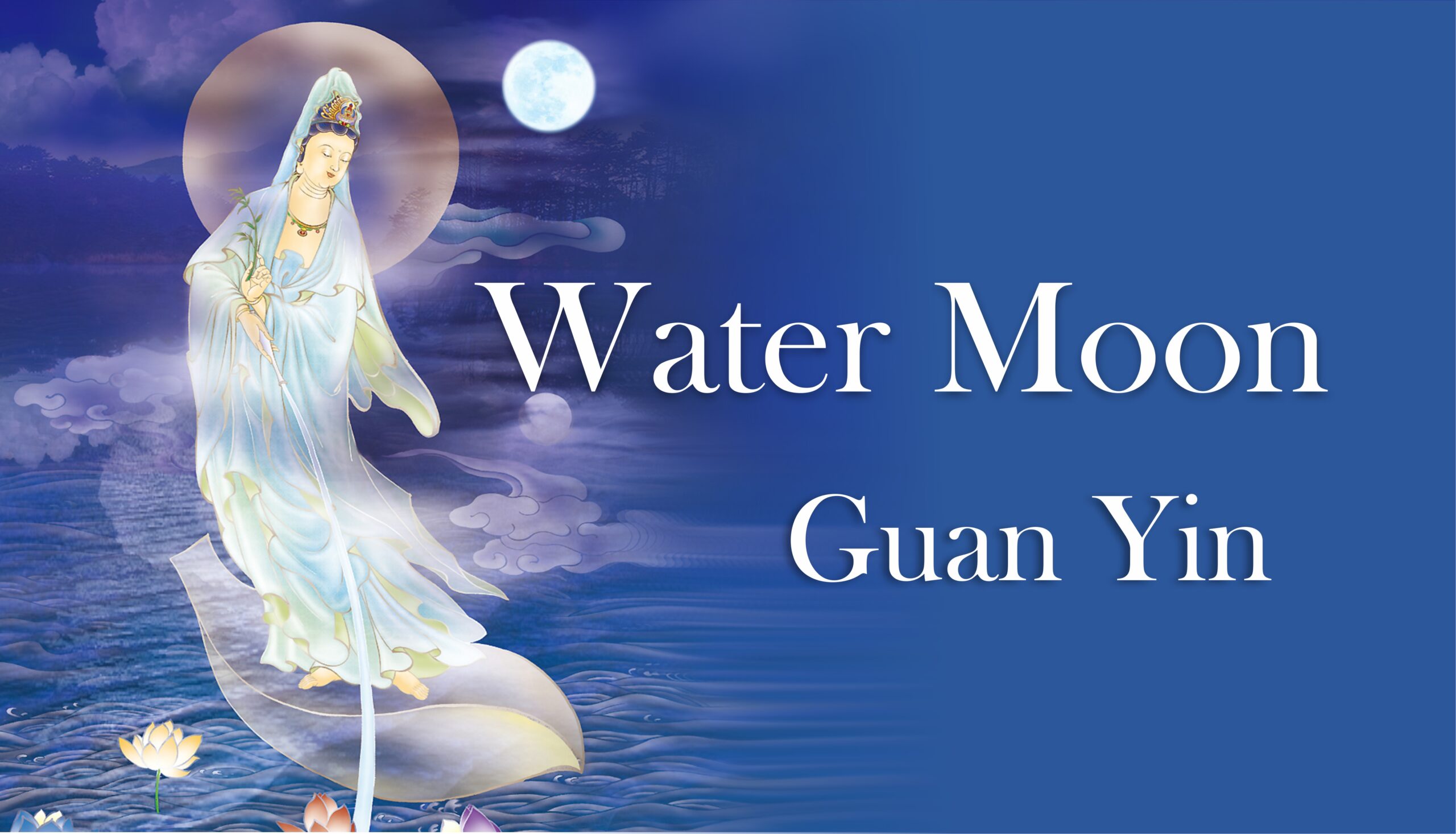

Guan Yin is also known as patron Bodhisattva of Putuo Shan (Mount Putuo), mistress of the Southern Sea and patroness of fishermen. As such she is shown crossing the sea seated or standing on a lotus or on the head of a dragon.

The dragon being an ancient symbol for high spirituality, wisdom, strength, and divine powers of transformation.

LEGENDS

GUAN YIM AND SHAN TSAI

Shan Tsai (also called Sudhana in Sanskrit) was a disabled boy from India who was very interested in studying the Buddha Dharma. When he heard that there was a Buddhist teacher on the rocky island of P’u-t’o he quickly journeyed there to learn. Upon arriving the island, he managed to find Bodhisattva Guan Yin despite his severe disability.

Guan Yin, after having a discussion with Shan Tsai, decided to test the boy’s resolve to fully study the Buddhist teachings. She conjured the illusion of three sword-wielding pirates running up the hill to attack her. Guan Yin took off and dashed off to the edge of a cliff, the three illusions still chasing her.

Shan Tsai, seeing that his teacher was in danger, hobbled uphill. Guan Yin then jumped over the edge of the cliff, and soon after this the three bandits followed. Shan Tsai, still wanting to save his teacher, managed to crawl his way over the cliff edge.

Shan Tsai fell down the cliff but was halted in mid air by Guan Yin, who now asked him to walk. Shan Tsai found that he could walk normally and that he was no longer crippled. When he looked into a pool of water he also discovered that he now had a very handsome face. From that day forth, Guan Yin taught Shan Tsai the entire Buddha Dharma.

GUAN YIN AND LUNG NUE

Many years after Shan Tsai became a disciple of Guan Yin, a distressing event happened in the South Sea. The son of the Dragon Kings (a ruler-god of the sea) was caught by a fisherman while taking the form of a fish. Being stuck on land, he was unable to transform back into his dragon form. His father, despite being a mighty Dragon King, was unable to do anything while his son was on land. Distressed, the son called out to all of Heaven and Earth.

Hearing this cry, Guan Yin quickly sent Shan Tsai to recover the fish and gave him all the money she had. The fish at this point was about to be sold in the market. It was causing quite a stir as it was alive hours after being caught. This drew a much larger crowd than usual at the market. Many people decided that this prodigious situation meant that eating the fish would grant them immortality, and so all present wanted to buy the fish. Soon a bidding war started, and Shan Tsai was easily outbid.

Shan Tsai begged the fish seller to spare the life of the fish. The crowd, now angry at someone so daring, was about to chase him away from the fish when Guan Yin projected her voice from far away, saying “A life should definitely belong to one who tries to save it, not one who tries to take it.”

The crowd realizing their shameful actions and desire, dispersed. Shan Tsai brought the fish back to Guan Yin, who promptly returned it to the sea. There the fish transformed back to a dragon and returned home. Paintings of Guan Yin today sometimes portray her holding a fish basket, which represents the afore mentioned tale.

But the story does not end here. As a reward for Guan Yin’s help saving his son, the Dragon King sent his daughter, a girl called Lung Nue (“dragon girl”), to present to Guan Yin the ‘Pearl of Light’. The ‘Pearl of Light’ was a precious jewel owned by the Dragon King that constantly shone. Lung Nue, overwhelmed by the presence of Guan Yin, asked to be her disciple so that she might study the Buddha Dharma. Guan Yin accepted her offer with just one request: that Lung Nue be the new owner of the ‘Pearl of Light’.

In popular iconography, Lung Nue and Shan Tsai are often seen alongside Guan Yin as two children. Lung Nue is seen either holding a bowl or an ingot, which represents the Pearl of Light, whereas Shan Tsai is seen with palms joined and knees slightly bent to show that he was once crippled.

LEGEND OF MIO SHAN

Given that Bodhisattva are known to incarnate at will as living people according to the sutras, the princess Miao Shan is generally viewed as an incarnation of Avalokitesvara (Guan Yin).

Another story describes Guan Yin as the daughter of a cruel king who wanted her to marry a wealthy but uncaring man. The story is usually ascribed to the research of the Buddhist monk Chiang Chih-ch’i in 1100 AD. The story is likely to have a Taoist origin. Chiang Chih-ch’i, when he penned the work, believed that the Guan Yin we know today was actually a Buddhist princess called Miao Shan, who had a religious following on Fragrant Mountain. Despite this, however, there are many variants of the story in Chinese mythology.

According to the story, after the king asked his daughter Miao Shan to marry the wealthy man, she told him that she would obey his command, so long as the marriage eased three misfortunes.

The king asked his daughter what the three misfortunes were that the marriage should ease. Miao Shan explained that the first misfortune the marriage should ease was the suffering people endure as they age. The second misfortune it should ease was the suffering people endure when they fall ill. The third misfortune it should ease was the suffering caused by death. If the marriage could not ease any of the above, then she would rather retire to a life of religion forever.

When her father asked who could ease all the above, Miao Shan pointed out that a doctor was able to do all these.

Her father grew angry as he wanted her to marry a person of power and wealth, not a healer. He forced her into hard labour and reduced her food and drink but this did not cause her to yield.

Every day she begged to be able to enter a temple and become a nun instead of marrying. Her father eventually allowed her to work in the temple, but asked the monks to give her very hard chores in order to discourage her. The monks forced Miao Shan to work all day and all night, while others slept, in order to finish her work. However, she was such a good person that the animals living around the temple began to help her with her chores. Her father, seeing this, became so frustrated that he attempted to burn down the temple. Miao Shan put out the fire with her bare hands and suffered no burns. Now struck with fear, her father ordered her to be put to death.

In one version of this legend, when Miao Shan was executed, a supernatural tiger took her to one of the more hell-like realms of the dead. However, instead of being punished by demons like the other inmates, Mio Shan played music and flowers blossomed around her. This completely surprised the head demon. The story says that Miao Shan, by merely being in that hell, turned it into a paradise.

A variant of the legend says that Miao Shan allowed herself to die at the hand of the executioner. According to this legend, as the executioner tried to carry out her father’s orders, his axe shattered into a thousand pieces. He then tried a sword which likewise shattered. He tried to shoot Miao Shan down with arrows but they all veered off.

Finally in desperation he used his hands. Miao Shan, realizing the fate the executioner would meet at her father’s hand should she fail to let herself die, forgave the executioner for attempting to kill her. It is said that she voluntarily took on the massive karmic guilt the executioner generated for killing her, thus leaving him guiltless. It is because of this that she descended into the Hell-like realms. While there, she witnessed firsthand the suffering and horrors beings there must endure and was overwhelmed with grief. Filled with compassion, she released all the good karma she had accumulated through her many lifetimes, thus freeing many suffering souls back into Heaven and Earth. In the process the Hell-like realm became a paradise. It is said that Yanluo, King of Hell, sent her back to Earth to prevent the utter destruction of his realm, and that upon her return she appeared on Fragrant Mountain.

Another tale says that Miao Shan never died but was in fact transported by a supernatural tiger, believed to be the Deity of the Place, to Fragrant Mountain.

The Legend of Miao Shan usually ends with Miao Chuang Yen, Miao Shan’s father, falling ill with jaundice. No physician was able to cure him. Then a monk appeared saying that the jaundice could be cured by making a medicine out of the arm and eye of one without anger. The monk further suggested that such a person could be found on Fragrant Mountain. When asked, Miao Shan willingly offered up her eyes and arms. Miao Chuang Yen was cured of his illness and went to the Fragrant Mountain to give thanks to the person. When he discovered that his own daughter had made the sacrifice, he begged for forgiveness. The story concludes with Miao Shan being transformed into the Thousand Armed Guan Yin, and the king, queen and her two sisters building a temple on the mountain for her. She began her journey to heaven and was about to cross over into heaven when she heard a cry of suffering from the world below. She turned around and saw the massive suffering endured by the people of the world. Filled with compassion, she returned to earth, vowing never to leave till such time as all suffering has ended.

After her return to Earth, Guan Yin was said to have stayed for a few years on the island of Mount Putuo where she practised meditation and helped the sailors and fishermen who got stranded. Guan Yin is frequently worshipped as patron of sailors and fishermen due to this. She is said to frequently becalm the sea when boats are threatened with rocks. After some decades Guan Yin returned to Fragrant Mountain to continue her meditation.